Colombia without asbestos: a historic landmark for public health

For forty years, the dangers of asbestos have been widely known internationally. However, in Colombia, it was not possible to convince several congressmen of what had been proven throughout the world: that these minerals are carcinogenic, there is no such thing as safe use, and the issue has nothing to do with industrial security. It is instead a public health matter, and this fiber is completely substitutable. Thanks to these points being persistently presented, finally on July 11, 2019 the president of Colombia Iván Duque approved Law 1968 —Ley Ana Cecilia Niño— which banned the use of asbestos in the country from January 1, 2021. This is one of the most important health-related achievements in recent years. For the Universidad de los Andes, everything began in 2009 when an informal meeting between María Fernanda Cely-García (at that time a master’s student) and professor Juan Pablo Ramos-Bonilla, who were both part of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, decided to research the risks associated with asbestos use in Colombia.

Over time, many more members of the Uniandino community joined this research including professors from the Department of Engineering and Medicine and dozens of undergraduate and post-graduate students from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. They collaborated with the Colombian Neurological Foundation, the Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá and researchers from Johns Hopkins University, the Italian National Institute of Health, the Universities of Turin and Bologna, and the French Research Institute for Development. As a result of the Universidad de los Andes’ efforts to explain the problem, on October 1, 2015, professor Ramos-Bonilla was invited by senator Nadia Blel to provide scientific arguments to legal discussions about prohibiting asbestos in the country. With his supporting documentation, the researcher made many points and, one-by-one, shattered the arguments made by the industry representatives and some congressmen who opposed the ban.

This added to many other people’s efforts who had already been pushing for a ban on asbestos: senator Nadia Blel, leader and sponsor of the bill in congress; the representative of the chamber Mauricio Toro; and the activists Daniel Pineda from the Fundación Ana Cecilia Niño, Silvia Gómez from Greenpeace Colombia, and Guillermo Villamizar from the Fundación Colombia Libre de Asbesto. Later, Juan Carlos Guerrero from the Observatory of Collective Action Networks at the Universidad del Rosario also joined the campaign. It was a tough fight that required scientific arguments, strong warnings, evidence, support, and debates. But why had it not been prohibited before? The discussion reached Colombia late despite Asbesto Crisotilo’s report published by the World Health Organization in 2015, which states that there are 125 million people in the world who are exposed to asbestos in their place of work, and it is estimated that the illnesses related to this mineral (lung cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis cause 107,000 deaths a year. Additionally, according to a report from the National Institute of Cancerology published in 2018, it is calculated that, 350 people die in the country each year from lung cancer as a result of being exposed to this material. The epidemiological observatory Global Burden of Disease states that 397 died in 2016. In the 77 years that the industry has existed, it has installed more than 300 million square meters of tiles and more than 40,000 linear meters of asbestos-cement piping.

In order for the ban to be finally lifted, there were a total of eight failed legislative projects, 12 years of arguments, unified concepts from four ministries, and a countless number of clinical cases (the issue has been under-registered in Colombia). Also decisive was Greenpeace Colombia’s determined activism, which mobilized citizens so that they could send 40,000 emails and make 2,500 calls to congressmen as well as publish 220 items in the press. The business lobby played an important role in the debates. Several congressmen showed their preoccupation for the industries that they saw being affected by the approval of the law and for close to 250 families from the asbestos mine in Campamento, Antioquia who would lose their livelihood. The news item “Why does Colombia not prohibit asbestos?” published by Cerosetenta and the Center for Journalism Studies at Los Andes states that this is the only asbestos mine in Colombia and services about 40% of the demand for these minerals in the country.

Also, according to researcher María Fernanda Cely, there are factories with this product in Bogotá, Barranquilla, and Yumbo. Private concerns disguised as public interest, the use of questionable scientific evidence, and misinformation from those who contradict the law were strong obstacles that the leaders of this struggle needed to break down. They faced a difficult situation given the disease’s long latent period as its onset may be many years after the initial contact with this material, which makes it very difficult to link the disease to asbestos exposure. It seems that in congress the victims’ direct and indirect voices –people living close to tile factories as well as factories that contain other products with this material or people who lived with family members who worked in these industries and who suffered from diseases including mesothelioma and asbestosis– were not enough to combat this public enemy.

A fundamental part of the strategy was carried out by activist groups and their diffusion strategies. There were demonstrations, sit-ins, online petitions, constant activity on social networks, symbolic gestures, and even long days in the halls of congress where one-by-one members stated to support the initiative. Academia contributed to this through the power of ideas. Alejandro Gaviria, vice-chancellor of Los Andes, in the forum History and Challenges of Banning Asbestos in Colombia, which took place in June 2019, summarized the situation in the following words: “The successful completion the project is a clear demonstration of the power of academia as an instrument of social change, of the power of research in debates and the democratic deliberation to change society, of the power academia can have when it transcends the dialogue of specialists and engages in democratic debate for everyone’s benefit”. Now for the implementation: a huge technical and economic challenge that has not yet been fully measured. The struggle continues and the leaders press on as it will sadly take several generations from when the law is signed until the moment when there is zero risk from asbestos exposure.

María Fernanda Cely, postdoctoral researcher at the Universidad de los Andes, says that “Banning asbestos in not the final solution. It just stops the growth of the problem. We need to recognize that we have, and we are going to have a public health problem for many years to come. We are only just beginning to measure the problem. This shows us the ways to face health challenges”.

Banning asbestos in not the final solution. It just stops the growth of the problem.

Banning asbestos in not the final solution. It just stops the growth of the problem.

SIGNS OF ALARM

- More than 90% of asbestos used in Colombia is used in the construction and motor sectors.

- The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies all types of asbestos as being carcinogenic in humans.

- A study that was led by the Universidad de los Andes over the last four years concluded that in the municipality of Sibaté (Cundinamarca) there is a high number of cases of pleural mesothelioma, which is a cancer directly related to asbestos exposure.

OTHER STUDIES: Everaldo Lamprea, coordinator of the Legal Clinic of Environment and Public Health at the Universidad de los Andes, contributed to the debate in congress with a research project that supported the need for an immediate ban on the exploitation, use, and commercialization of asbestos in Colombia. He pointed out that this should be accompanied by through regulation to mitigate and repair the effects of using this material in constructing social and priority interest housing. “It is unacceptable that construction projects are being carried out using materials that contain asbestos for housing for this population that should be protected. In other words, it is inadmissible that the State accepts and promotes the construction of social and priority interest housing with materials that cause cancer”, said the researcher when he spoke in congress.

Ana Cecilia Niño died in January 2017. She fell victim to lung cancer, which was associated with her 17-year exposure to asbestos in Sibaté (Cundinamarca).

Related news

The country’s first metabolomics center, which is one of the first in Latin America, was inaugurated in the Universidad de los Andes.

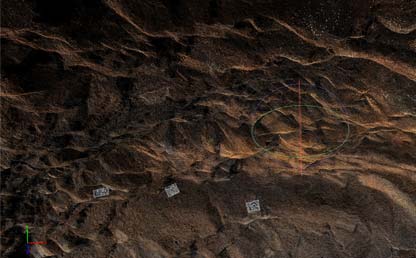

Experts research caves in Patagonia. Andrés Burbano from the Department of Design at the university carried out the photogrammetry of the site.

Design students win the Biodesign Challenge, which is an award endorsed by Peta, the Stella McCartney brand, and the Stray Dog Capital corporation.

Otras noticias

- Professor from Los Andes is awarded the Sabin Award for Primate Conservation

- Synthetic drugs turn zombies from fiction into reality

- A project that uses fish to study Chagas disease has been presented with an award

- Andinobates victimatus: the frog for the victims of the conflict

- Travel diary for a green planet

Share