Note: This analysis is the result of research projects that the professor has undertaken, including fieldwork in the regions.

By Diana Gómez Correal

Assistant professor in the Cider/ Uniandes

On Thursday August 29, Colombia woke up to the news that the FARC EP was, once again, going to take up arms: according to Iván Márquez, it would be a second Marquetalia. Different ideas about and answers to this situation circulated on Twitter, WhatsApp, and other media outlets. The most impacting was journalist Enrique Santos’ response on Twitter: “I never thought that I would have to witness the emergence of the FARC twice in my lifetime”.

Faced with this crisis, together with the celebration of the International Day of Peace, I wanted to propose seven key points to help understand the complex reality of war and peace in Colombia.

But first some brief context: The reorganization of the structure of the FARC did not happen last Thursday. The initial seed was sown in how the peace process in Havana unfolded as certain sectors of this guerrilla organization did not agree with the very idea of negotiation.

The situation was intensified by the triumph of the No vote, which turned its back not only on the peace process but also on the huge number of victims and citizens who voted Yes in the plebiscite. Subsequently, certain decisions taken during the Fast Track and its implementation set off alarms about the legal security of ex-guerrillas and asymmetrical treatment in the peace process’ justice mechanism.

As such, the armed reorganization of the FARC is not only the result of a group of guerrillas who favor armed struggle as a political strategy, a vision which is clearly debatable both politically and ethically; it is also the Colombian State and certain politicians, and citizens’ answer to the simple, but at the same time, complex idea of peace.

The most significant key to achieving peace and war in Colombia is that these must be fully comprehended and analyzed and not just loosely understood based on primary visceral reactions that result in the continuation of the guerrilla.

The second key point is that people’s understanding must be based on a complex thinking rather than dichotomous, simplistic, or Manichaeist thinking. War and peace are not black and white.

War and peace are linked together, they are relational, and this means that they are nuanced.

The fourth key point relates to it only being possible to approach both using a procedural lens. War and peace do not just happen on any given day. They have to be cultivated. They question each other, they modify each other in a process that lasts decades or even centuries. The violence in Colombia was an inherent part of the creation of the nation State, and, as such, it should be understood as a process.

Returning to the key aspect of complexity, it is worth noting that the war did not end when the peace process was signed. The guerrillas from the ELN and the EPL as well as the FARC dissidents did not just disappear.

The current war is ever more degraded by how long it has lasted as well as the diversity of actors involved. Today, it is fueled by groups of drug traffickers with international connections, by extreme right-wing groups responsible for several of the assassinations and attacks against social leaders, by both formal and informal paramilitary organizations that have not completely disappeared as a result of demobilization in the past decade, by the release of paramilitaries who have now served their sentences under the framework of justice and peace, and, unfortunately, by some State institutions.

War and peace in Colombia cannot solely be understood from a Bogotá-perspective. The view from the capital seems to not see or not want to see that the country has been burning for months (years). On the Caribbean coast, cities and departments such as Santa Marta, Cesar, and Córdoba have witnessed a violence with different nuances that seeks not only to control production and trafficking of drugs but also the territorial control of the population. It also impedes the peace process making any progress.

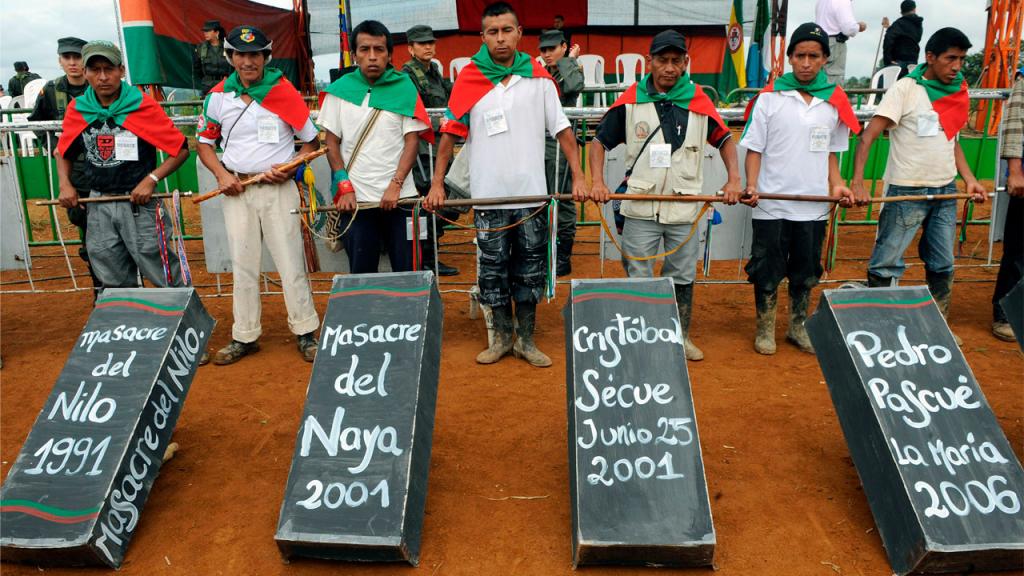

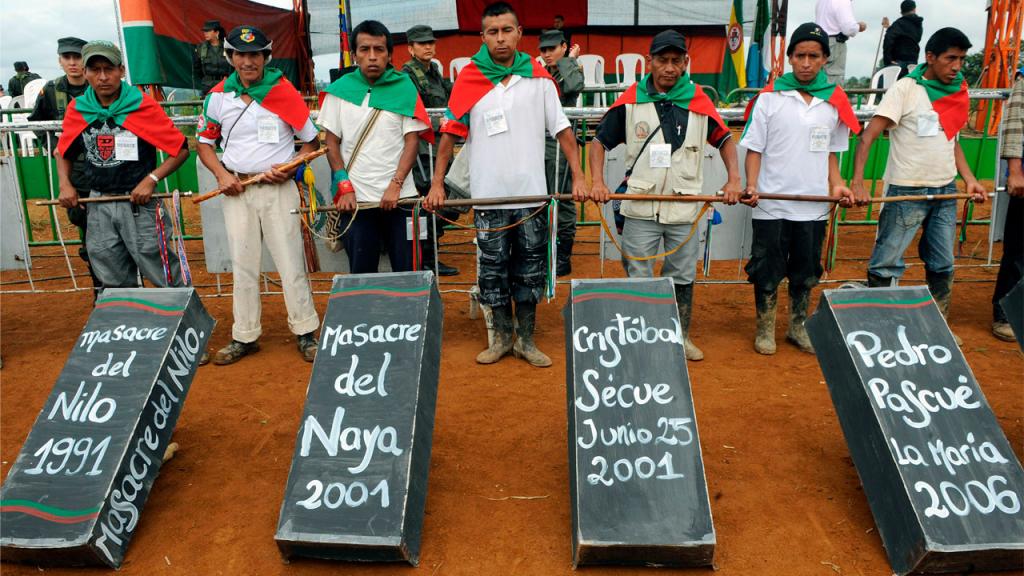

Chocó, Cauca, the indigenous and Afro communities, campesinos, leaders, and victims have all suffered from extreme violence before Thursday August 29. This should make us ask ourselves: Why are these people and these places once again a military objective?

Let us move away from understanding peace and war as a spectacle. Márquez and Santrich appear in their video announcing their defensive war by displaying weapons and military uniforms, and becoming spokespeople for those of us who have not given them this authority. They have turned into messiah Rambo’s whose message of war and spectacle we should not replicate because it escalates several of their objectives, including the militarization of society.

Imagining and making peace based on committed hope. This implies recognizing that peace is a process that is so not easy to achieve, and it will only be possible if the broad majority bet on peace building in their daily lives. This means that violence needs to be understood in all its complexity, and something needs to be done to contribute to weaving a society that no longer boasts about militarization, rifles, pistols, threats, murders, disappearances, military strategies, and attitudes of war in politics and daily life.

For this, we need politicians and citizens who are able to distance themselves from the daily and corporal habitus of war to firmly believe in a transformative peace. This requires all the actors related to the war and different types of violence to be rejected, showing solidarity with all the victims, and supporting those who have decided to distance themselves from getting involved in arms to bet on a different future.

To protect and promote child development in communities affected by violence as well as fostering love and early childhood care in Colombia, professor

For forty years, the dangers of asbestos have been widely known internationally. However, in Colombia, it was not possible to convince several congres

Experts in Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Colombia, met at the Second Regional Workshop on Drug Production, Trafficking, and Policy in the Ande

Otras noticias

Share